By

Roldán Tumi has come a long way. Since the day he decided to leave his community, a series of experiences have made him the person he is today: an indigenous anthropologist who understands the challenges facing his people and is willing to work in service of his community. In this edition of #storiesofindigenousyouth we invite you to get to know him a bit better.

Roldan belongs to the Matsés people. The Matsés accepted contact with western society only relatively recently, in the late 1960, when missionaries settled on their land. He grew up in the remote Matses village of Buenas Lomas Antigua, deep in the forest, close to the boarder with Brazil. His village life consisted of accompanying his mother to their field, dedicating himself to agriculture and fishing. In his community, the main language spoken is Matsés; therefore, Roldán began to learn Spanish only when he felt the need to leave his community to start looking for a job that would allow him to have an income. This search led him to experience firsthand the injustice of the loggers, the harshness of the army, discrimination, and the loneliness of being in an unknown city with a culture and languages foreign to his own.

The dream of studying at the university arose when he found out about the “Beca 18”, a scholarship offered by the Peruvian government, a dream that turned into determination when he found out that he did not meet the requirements to be eligible for it. He still remembers what he told his brother when he suggested him to return to their community, "No, I told him, because I am committed to studying. I wanted to return to the community as a professional”.

Despite knowing almost nothing about what anthropology was, he learned to fall in love with it while studying it, regardless of the challenges of the Spanish language. "I liked studying, I felt good. When my classes started, I was always punctual, I liked to study, although when I took my first exam I got an 08 and I felt very bad." The low percentage of indigenous students who complete their studies is a largely due to the unfavorable living conditions they face in the city and an education that does not strive to incorporate the needs of these young people. However, it was Roldán's determination that led him to persevere, "sometimes I would go without eating, but even though I was like that I was not discouraged, I wanted to continue. My dream was to study until I finished my degree, I think I always thought 'I want to finish my degree, I want to study’”.

Learning about the Organization of Students of the Indigenous Peoples of the Peruvian Amazon (OEPIAP, by its Spanish acronym) not only gave him a place to live, but also the support of other indigenous peers with similar experiences to his, "Ronal always encouraged me to continue studying. He would tell me that all the young indigenous people have been through this, look how they are doing now. We've been there too. I know you're going to do it, you just have to study, don't pay attention to the bad people. When you realize it, you will already be close to ending’” which shows the importance of this organization in providing not only material living conditions, but also a support network.

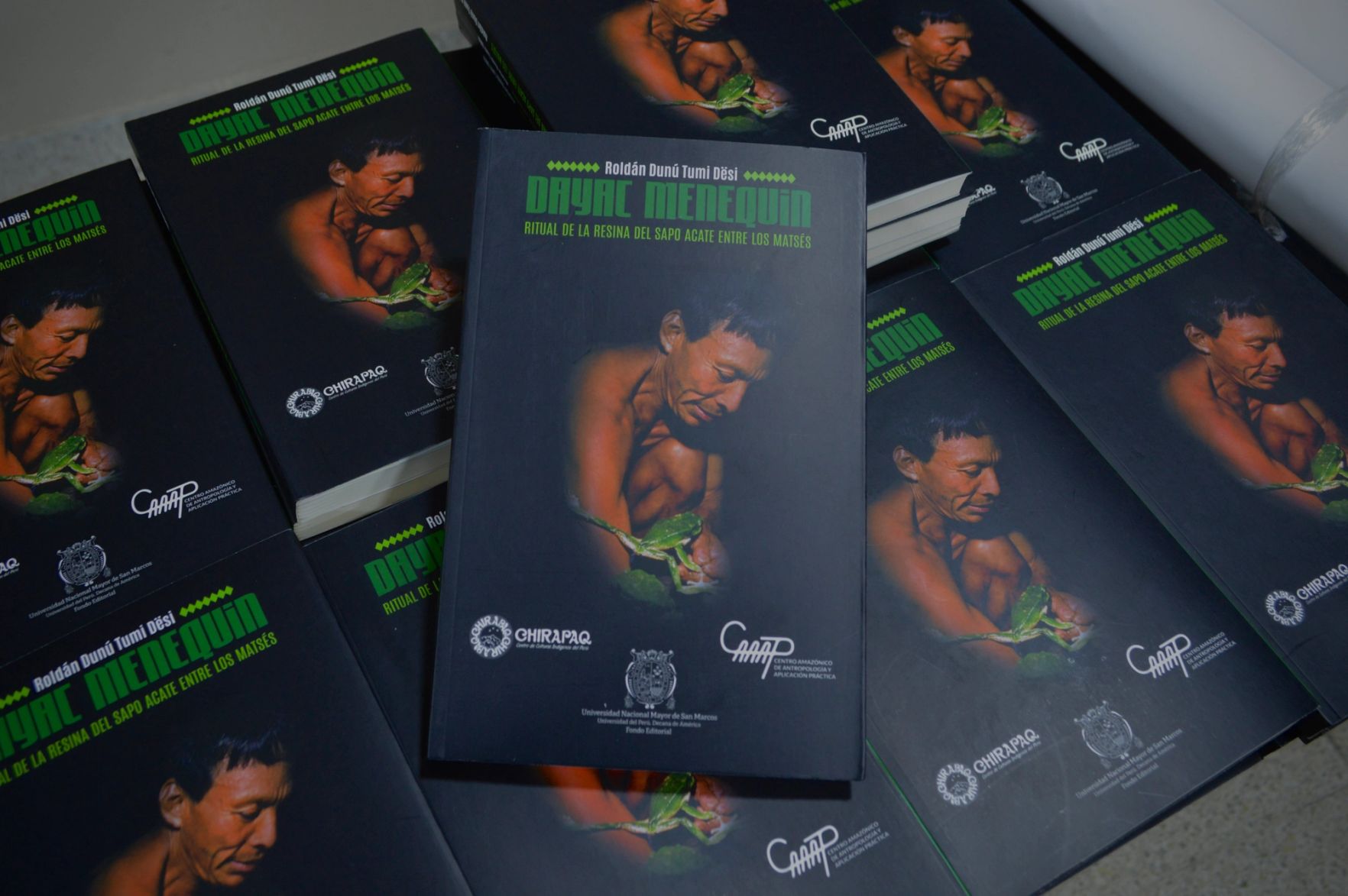

His interest in researching the ritual practice of toad venom acate, typical of the Matsés people, began thanks to a college paper, "I looked for information online. I found a lot of information, but it wasn´t called toad venom, the popular name was kambó. It was not research, but blogs that worked selling the resin on Facebook". This situation, and finding information about other research in Brazil, led him to want to do the same in Peru, "I wanted to know who the people are using it and how, and compare it to how the Matsés are using it [...]. I, coming from the Matsés people, wanted to tell, to talk about the poison of the toad".

For Roldán, this research meant to return to his community: his family, his language, his culture, what was known for him. This experience of returning also meant going back to work on the land. “When I went back to my community some of my schoolmates, some of my fellow “paisanos”, told me 'I have heard that you have a university degree, but I don't see you as an anthropologist, you are the same'. I had gone to the chacra to work, and they told me 'you are doing the same, you have not changed anything, you are doing the same as you did before'", and this situation led him to reflect on his role as an indigenous anthropologist, "that is anthropology, that's what I told them. That's what we do so as not to lose what we were before. I, as an indigenous anthropologist, am not going to feel different for being a professional and trying to be "better" [...] I am an anthropologist because I have finished my career, it does not mean that my life will be different". For his “paisanos”, a Matsés professional is also an opportunity to have one of their own working or participating in projects that are developed in the area, as well as a reference for other young people.

Thanks to the effort he put into his research, he was able to complete his thesis and become the first Matsés anthropologist in Peru, which gave him a media attention that only reflected how difficult it is for these young people to succeed in an educational system that continues to resist being intercultural beyond mere discourse.

His research also led him to reflect on the spreading of indigenous knowledge and traditions today, and the lack of credit they get for it, "I always think that this should not happen. Indigenous knowledge should be protected, it should not go out so easily to other places, to other countries [...] The government should worry about how we can protect it, so that there is more control and that it cannot be taken away, because currently the toad poison is everywhere, in different countries [...] I know that in the future other indigenous knowledge that is not yet known will also be taken by other people".

These concerns also extend to the future of his people. Roldán would like to contribute with some initiative that allows them to generate economic income in a sustainable way, "because now we, as indigenous people, not only live eating meat or yucca [...] I want to do a project that generates jobs in the community itself, so that they can work. I don't think 'Oh, these are indigenous people, so they have to live forever only protecting their territory'". As an indigenous, Roldán understands that, like all societies, indigenous peoples have - and will continue to - experience changes and adapt to them, for which it is important that they have tools that allow them to develop with autonomy, “I think that we as indigenous people cannot continue asking NGOs to support us so that our children can go to the city, but that they themselves can also contribute so that their children can prepare and study at the university".

His strong intrinsic motivation and commitment push him to meet new professional challenges. Last month, Roldan, with the support of Chirapaq, The National University of San Marcos, and The Amazonian Center for Anthropology and Practical Application (CAAAP), published the book "Dayac menequin" based on his thesis research. Soon, he will begin studying a master's degree in Anthropology in Brazil, "I don't lose the desire to return to my community. I always want to work in my village, but now I plan to study for my master's degree".

If you are interested in purchasing the book "Dayac menequin", you can contact Roldan by writing to him at:

roldantumi@gmail.com

We believe in intercultural education as a means of creating an inclusive, diverse, and equitable society that honors and celebrates its constituent cultures and identities. Since 2014, we have been working in partnership with OEPIAP promoting interculturality in the educational system, providing support to improve access to higher education and sound basic living conditions for the indigenous students in the city of Iquitos.